The call came late. After 10 p.m. at least, and perhaps later.

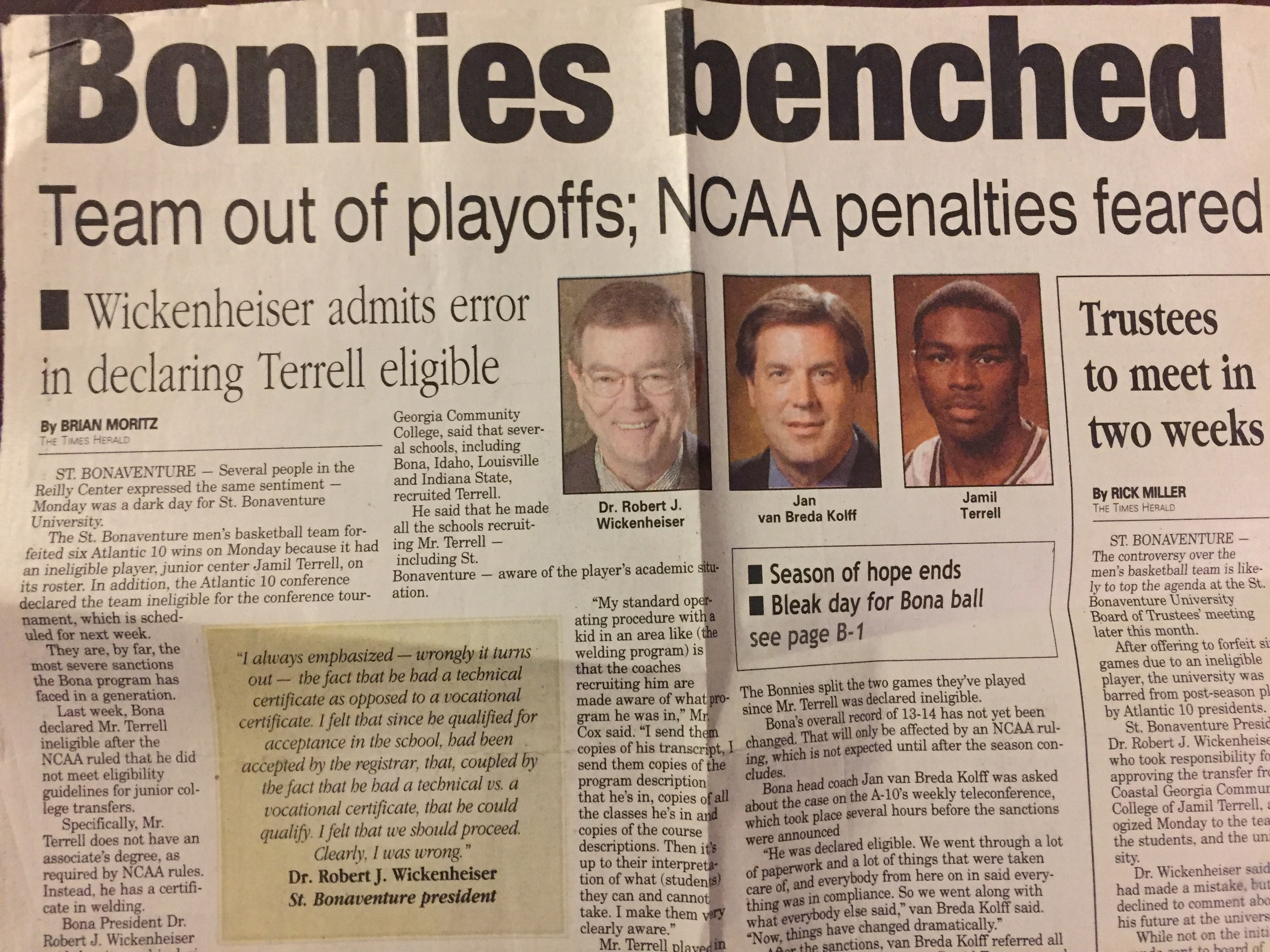

This was March 3, 2003. It was already the biggest day of my journalism career. The Jamil Terrell-eligibility scandal, which had been festering in the background of the St. Bonaventure men's basketball season, had blown up that day. The team had forfeited six victories and was banned from the Atlantic 10 tournament after using a player all year who had been academically ineligible after earning a welding certificate from junior college.

I knew I had a scoop for the next day's paper (this was back when scoops were measured like this). I had spoken to Terrell's junior college coach, Gerald Cox, who told me that the Bona coaches knew very clearly that Terrell's certificate was not equivalent to an associate's degree (the crux of the NCAA eligibly issue). This was already the biggest story of my career.

Then, late at night as I was piecing together this huge story, the phone rang.

Hi Brian. Robert Wickenheiser.

It was the university president, the man who's name is on my undergraduate diploma, the man who OK'd Terrell's transfer at the request of the basketball coaches and over the objections of his athletic director and compliance officer, the man who was ultimately responsible for a scandal that landed the program on probation, the man who was at times the loudest and most vocal basketball fan at St. Bonaventure who ultimately set the program back nearly a decade.

My mind's been going back to that phone call the last few days, since hearing that Wickenheiser had died at age 72. That call was, to my knowledge, one of the final interviews Wickenheiser gave. He spoke to Real Sports with Bryant Gumble a year later, but I believe that's it.

A career in journalism is inextricably connected to a handful of people. For me, Wickenheiser was one of those people.

He was a controversial figure at the school long before Jan van Breda Kolff and staff had started looking for a big man to fill out their speedy but undersized lineup. In 1994, when he became the college's first lay president, he laid off 17 tenured professors. The move probably kept the college open at a time of financial exigency, but it angered faculty and set a tone of distrust for his entire tenure (now, being on the faculty side of the ledger, I can't imagine that happening). He helped raise money for a beautiful on-campus arts center and was the president when men's basketball returned to the NCAA tournament for the first time in 22 years. But he also reportedly helped run a popular coach off campus, setting the stage for the van Breda Kolff era and the ensuing scandal.

Wickenheiser was, in many ways, a reporters' dream. The man spoke in paragraphs. He was intelligent, as accessible as any college president is, and had strong opinions. You may not agree with him, but he was never shy about sharing them. He also insisted on being referred to as Dr. Robert J. Wickenheiser in print (full name), to the point where he briefly refused to speak to our paper's education reporter because she hadn't used his middle initial (and this is why, to this day, my old boss Chuck Pollock always calls him Bob Wickenheiser).

So while I wasn't really expecting that phone call from him on March 3, 2003, I wasn't surprised. And in a way, I respected him for calling. This was the worst day of his professional life. He'd be fired six days later, and the only surprise is that it took that long. He sounded devastated on the phone, but we spoke for more than an hour - some off the record, but mostly on. He answered all of my questions except for how he got involved, since player eligibility isn't usually something presidents get involved with (his son, Kort, was an assistant on the men's basketball staff, so there was never a huge question as to how it happened). "I'm not an expert in eligibility by any means," he told me, even though he unilaterally declared a player eligible. He took full responsibility for the scandal. He insisted it was a mistake on his part rather than outright cheating.

"Everyone makes mistakes, and this is one I regret. I regret it not for me and my future but because I have deeply offended the team and the players. I have too high regard for them, and for what they stand for at Bonaventure and what basketball stands for at Bonaventure, and I have too high a regard for Bonaventure. How do I feel about what I've done? I feel terrible. Words can't describle how I feel. I apologize to the team, to the students, to St. Bonaventure University, that I love dearly."

In the end, reasons or specifics don't matter. It was bad. He knew it. I knew it. Everyone knew it.

But still, he called me back. He answered my questions.

In the end, that says something.