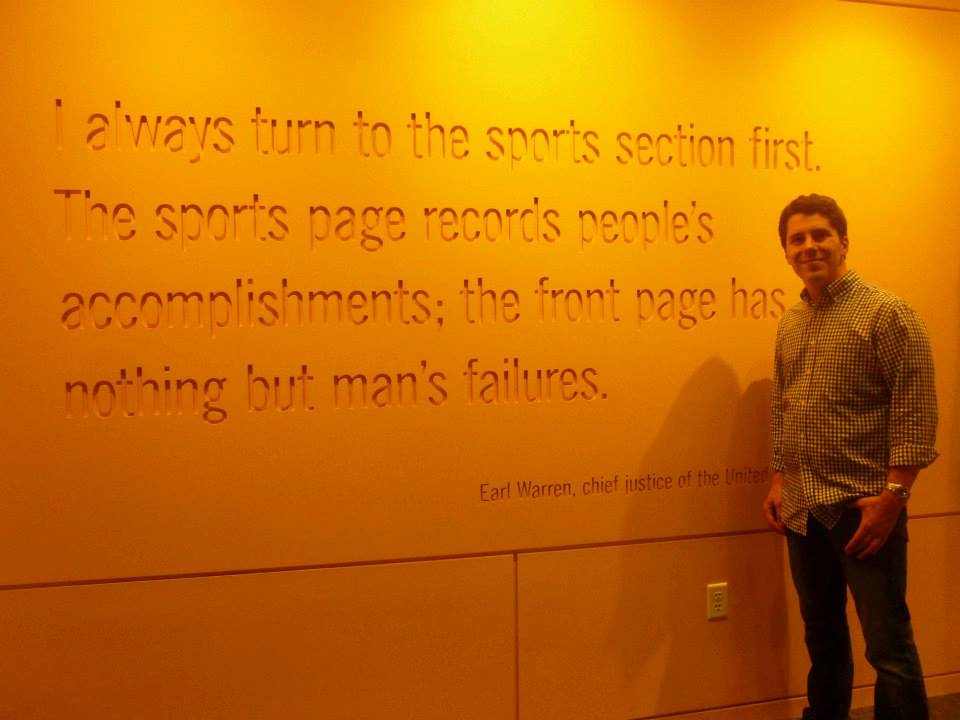

There’s a quote attributed to Earl Warren, the former chief justice of the Supreme Court of the United States: “I always turn to the sports section first. The sports page records people’s accomplishments; the front page has nothing but man’s failures” (Sports Illustrated, 1968).

It’s a quote that has long been used to celebrate the importance of sports journalism. It is carved into the wall at the Newseum, the Washington, D.C.-based museum dedicated to American journalism. It hangs on the wall near the sports desk in many college newsrooms. It serves as a reminder and a declaration that the sports page plays an important role in journalism.

But there’s a subtext to the quote, as well. If the sports page is the home for people’s accomplishments, then it can also be seen as the home for only positive news. The sports page is where people go to escape the problems of “the real world,” to read good news instead of the bad news that is perceived to fill the front page. A reading of that quote suggests that sports journalism’s role is that of a cheerleader, one that celebrates the good while ignoring the bad. It suggests that the proper attitude of sports journalists is to cheer for the home team, rather than being an objective look at a team’s successes and failures. It suggests that larger sociological issues like race, gender, sexuality, economic equality, and others—issues that often affect sports and athletes—have no place in the sports pages. Warren’s quote, while on the face is celebratory of sports journalism, can actually be read as a criticism of sports journalism in the face of traditional journalism norms and values.

The Warren quote is emblematic of the struggle to place sports journalism within the news landscape. Traditionally, sports journalism has been seen as the “toy department” of the newsroom. It’s seen as an area of interest, a topic people want to read about and something that’s important to the business of selling newspapers, but it’s not real journalism when compared with news and political coverage. Writing in 2006, Raymond Boyle described one of the central tensions of sports journalism as that balance between it being real journalism (following norms, practices, and ethics of the profession) and it being just entertainment or a promotional tool for the local teams.

David Rowe, writing in 2007, captured the balance of sports journalism:

The sports beat occupies a difficult position in the news media. It is economically important in drawing readers (especially male) to general news publications, and so has the authority of its own popularity. Yet its practice is governed by ingrained occupational assumptions about what “works” for this readership, drawing it away from the problems, issues, and topics that permeate the social world to which sport is intimately connected (p. 400).

(This post was originally published as part of my dissertation: "Rooting for the story: Institutional sports journalism in the digital age.")